It’s a funny thing, really, that after several decades of women’s history in the academic world, historians should still need to be told how to go about finding women. ‘Look to the edges’, exhorted Amanda Herbert in her keynote address for ‘Networking Early Modern Women’. This was no less than a call to arms, especially amidst the #femfog (in which a prominent medieval historian claimed that feminists intimidate and victimize men, obscuring manly good sense in a feminist fog).[1]

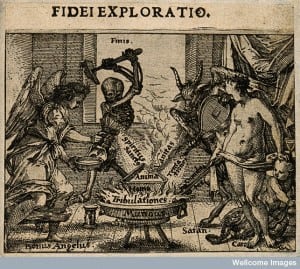

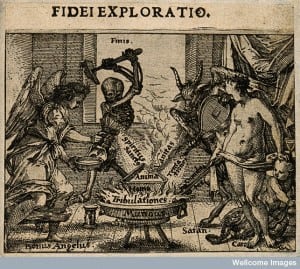

The origins of #femfog? C. Murer, c. 1600-1614. Image Credit: Wellcome Images, London.

The goal of the add-a-thon, hosted by the great Six Degrees of Francis Bacon project, was to add more women into the database’s networks. And the Sloane Letters team[2] was (virtually) there! As Hillary Nunn noted in a review of Six Degrees, there were initially few women in the database, in large part because the project drew heavily on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography when identifying networks.

Elizabeth Monck (née Cavendish), Duchess of Albemarle, after Unknown artist. Image Credit: NPG D30497, National Portrait Gallery, London. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

From a Sloane perspective, the Six Degrees database also lacked any of the women in Sloane’s networks–even though much of Sloane’s early patronage came from women. For example, Sloane was the Duchess of Albemarle’s household physician for several years after returning from Jamaica. The Duchess later married the Duke of Montagu, and Sloane was consulted by the extended Montagu family.

Sloane also corresponded with women about a range of subjects beyond medical treatment. Widows like Margaret Ray, Margaret Flamsteed, and Anna Hermann consulted him about bookselling and publishing. Some women, such as the Duchess of Bedford and the Lady Sondes, asked for advice about family matters. Other female correspondents shared an interest in natural philosophy; Cecilia Garrard, for instance, sent him specimens and the Duchess of Beaufort discussed botany (and, at her death in 1715, bequeathed him her herbarium). All of this I know through long familiarity with Sloane’s correspondence.

But what does the picture of women’s networks look like if we take a step back from individual letters to examine the cumulative data in the Sloane Letters database?

To prepare for the Six Degrees add-a-thon, research assistant Edward Devane extracted all of the Sloane Letters references to women who were born before 1699–the cut-off date for inclusion in the Six Degrees database. I also asked him to create a shortlist of women who had clearly strong connections with Sloane: women who appeared frequently, referred to social contact, or wrote several letters. There were 339 female individuals on the long list who were mentioned in the letters at least once. But for the shortlist? A mere twenty-seven women.

Look to the edge, indeed!

The group of strongly connected women picked up several crucial relationships, such as Sloane’s friendship with Lady Sondes; his old family connection to Anne Hamilton (dowager Countess of Clanbrassil); and his assistance of Margaret Ray, widow of Sloane’s good friend John Ray.

But the most important connections in Sloane’s life were only to be found in the margins. This was quite literally the case for his family relationships (wife and daughters) who appear in postscripts, along the lines of: ‘My humble service to your Lady and daughters’. There are also occasional references to his other female family members—mother, nurse, sisters, aunts… As for the Duchess of Albemarle, she was mentioned only a few times in a handful of letters from Peter Barwick.

Of course, it is not surprising that people whom Sloane saw frequently do not appear in the letters, but their absence obscures the social, family and patronage networks that would have been important to Sloane’s daily life. Although the women remain hidden as strong connections when extracting basic data, the Sloane Letters database can still be searched by name or relationship, which makes it easier to sift through the masses of correspondence to find scattered references to his family networks.

Image Credit: University of Cambridge Digital Library.

Then there are the female correspondents who didn’t even appear in the list at all because they signed their names using initials. Take, for example, J. Squire who wrote to Sloane in 1731. There is nothing in the letter that explicitly suggests that J. Squire was a woman. However, the linkage of the three names—Squire, Abrahm de Moivre and Sloane is telling. Jane Squire had a proposal to determine longitude, which attracted the interest of De Moivre and Sloane. How many other women are to be found lurking behind initials in the correspondence?

What we mean when we talk about networks might also need to be broadened when we look to the edge. Do we just trace important people with wide networks? Do we just trace those whose biographies can be verified? Just how inclusive should we be?

A family group of a woman and four children flanked on either side by figures of children. Engraving by Aug. Desnoyers after himself after Raphael. Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Sloane’s loose connections present a number of women who saw Sloane as a part of their network, even if the women did not play a meaningful role in his life. Mrs. E. Martin wrote to Sloane in 1725 and 1726 asking for his help in a person situation. Her lover, Mr. Knight, had abandoned her and their children to marry another woman. By 1726, the situation was worse: Mr. Knight had her confined, removed her child, and frozen his payments to her. Mrs. Martin noted that Sloane had once treated her. This was typical; there were several one-off letters from former patients asking for assistance, presumably because Sloane was one of the most important people they knew.

However, the names that Mrs. Martin dropped in the letters also suggest that she thought Sloane might have personal influence: Mr. Knight, Mr. Isted, and Mr. Meure. Isted was Sloane’s son-in-law, while Knight and Meure were friends of Isted and Sloane. Perhaps these other connections were a little too close, because Sloane dismissed her altogether:

I rec’d yors & am in no manner of condition either to advise or relieve you being perfectly a stranger to what you write & not in a possible way of helping you, being full of affairs in my own profession that I have neither time nor abilities to be assisting to you.

Mrs. Martin was, indeed, a woman found at the edge—of survival and social networks.

At first glance, looking at the list of letter-writers, women hardly factor in Sloane’s correspondence. There were women who wrote directly to Sloane, but most women appear only as subjects, mentioned by medical practitioners, family members or friends (their, er, networks?). One of the reasons that I developed the Sloane Letters database was to make those hidden women more findable; if we describe the letters beyond authorship, women’s stories and networks suddenly become visible.

And it is only by looking to the edges in the first place that the outlines of early modern women’s networks emerge, revealing how women were at the centre all along.

[1] David Perry has a good summary on #femfog and links to other criticisms here: http://www.thismess.net/2016/01/grab-your-balls-and-problem-with-blind.html

[2] The team included my University of Essex research assistants (Edward Devane and Evie Smith) and me.