To honour International Women’s Day today, I have decided to return to my roots as a women’s historian. I first became a historian for feminist reasons: to recover women’s past and to understand the relationships among culture, body, gender, and status.

The control women had over their bodies has often been a staple topic of feminism and women’s medical history. We love to dig out (largely nineteenth and twentieth century) stories about the horrors inflicted upon women’s bodies: clitorodectomies, forced sterilisation, and more. They make for chilling telling. Or perhaps we look back to Antiquity: women as monsters or inferior, inverted men. We find the tales about menstrual blood being poisonous. It’s easy, surrounded by such stories, to assume that the goal of medicine has been about controlling women.

But the reality is far more complicated.

In the early eighteenth century, the misogynistic medical theories of inferiority, for example, were seldom practiced. All bodies were treated as humoral bodies, with specific temperaments that were individual to a patient. Medicine was highly interventionist (and often ineffective) for both sexes. And, more to the point, medical practitioners were dependent on their patients for success. This was not just in terms of payment or patronage.[1] . In an age before anaesthesia, or even stethoscopes, doctors and surgeons were unable to look inside the living body: patients’ stories were invaluable tools in diagnosis. Women could have much control over their own health.

Promising? Not exactly. These women’s choices were still limited in a multitude of ways. The ability to make decisions about one’s own body, whether historically or today, is an important marker of women’s equality. An old argument, perhaps, but one that is as true now as ever. When talking about control in the modern world, it often comes down to topics such as abortion or female genital mutilation. The dullness of day-to-day inequality is easy to overlook when there are more pressing issues.

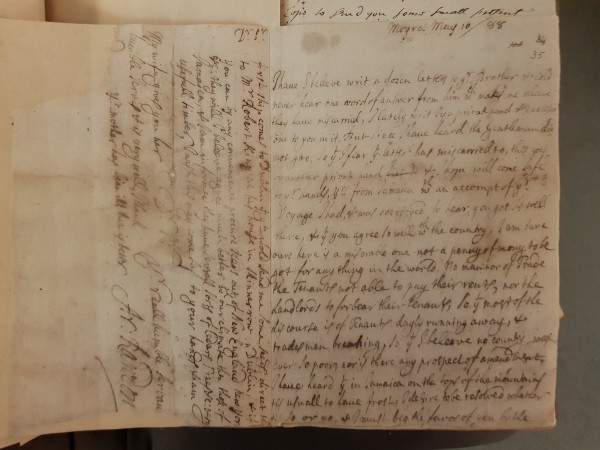

Back in the eighteenth century, the fundamental inequalities within society can often be seen within the household. Women might, for example, have been well-treated by physicians–but, as letters to physician Hans Sloane show, their ability to make medical decisions was limited by something even more fundamental: access to money.

John Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex (1816). From: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA (Wikimedia Commons).

A husband could decide when and how a woman saw a doctor. In 1715, physician William Lilly commented that his patient Lady Suffolk was well enough to travel to London from her countryside residence in order to see Sloane, but only “if my Lord thinks fitt to bring her”.[2] Even when a woman was pleased with her medical care, her husband might choose another course of treatment, as one unnamed doctor complained. He had been treating Lady Salisbury in 1727, who agreed with his recommendation that she should go to the countryside while she recuperated. Lord Salisbury, however, had other ideas. He dismissed the unnamed physician, instead turning over his wife’s care to Dr. Hale. No reasons were given for the change.[3]

Whether or not a woman received care was also up to her husband. Although the head of a household was obliged to provide medical care for everyone within it, the extent of the care needed was open to dispute.[4] Mrs A. Smith, for example, found that her treatments in Bath were useful, but her husband refused to continue paying. Someone, she believed, “has told Mr Smith that I am very well and I only pretend illness to stay in Towne”. Her dependence on Mr Smith’s decisions was clear. She noted that she was unhappy, since “all my Ease depends a pone Mr Smith’s opinion of me”. Worried that she would become more ill if her husband sent her to the countryside, she begged Sloane to intervene by “tell[ing] him how you thinke me”.[5]

Family members might try to help if they believed a woman’s health was being affected by her husband’s choices, but this was complicated and not always successful. The law, after all, ultimately upheld the power of a husband over his wife. Jane Roupell wrote to Sloane about her daughter, Lady Anne Ilay, on the grounds that her son-in-law had weakened her daughter’s health through his lack of care. Mrs. Roupell asked if Sloane might visit before seeing her daughter, so she could “tell you somthings that she is ashamed to tell her selfe”. It would be best, she thought, if her daughter could recover away from her husband–perhaps, she suggested, Sloane might recommend that Lady Ilay be sent to the countryside.[6]

The countryside in these four letters becomes alternatively a place of health, a place of isolation or a place of refuge. Although we’ve moved on a lot since the eighteenth century, there are two basic women’s health issues that underpinned these seemingly simple disputes about going to the countryside: access to health care and finances.

Most often, the Sloane correspondence provides examples of women’s families wanting the best for their wives and daughters, but women were always in precarious positions. Each woman came from a wealthy background and had doctors (such as Sloane) who were potential allies, but as the cases show, women could not simply choose what treatment they wanted without consulting their families. One thing was clear: it was ultimately up to their husbands what a woman’s medical treatment should be.

[2] British Library Sloane MS 4076, f. 14, 28 July 1715.

[3] British Library Sloane MS 4078, f. 304, 26 March 1727/8.

[4] Catherine Crawford, “Patients’ Rights and the Law of Contract in Eighteenth-century England”, Social History of Medicine 13 (2000): 381-410.

[5] British Library Sloane MS 4077, f. 37, n.d.