Showing page

1 of 305Next

The Sloane Correspondence contains several examples of curious medical cases, many of which were intended for publication in the Philosophical Transactions (which Sloane as secretary of the Royal Society edited for many years). One such case is that of Mrs Stevens of Maidenhead, aged 62. Surgeon Ralph Calep recounted her case in a letter to anatomist William Cowper, who in turn forwarded it to Sloane for publication.

Mrs Stevens became ill with a fever in November 1697. Within two weeks, she developed a swelling and numbness in her foot that spread up her leg. For a month, the attending physician treated her with remedies that theoretically should have helped according to early modern medical thought. The first treatment was a warm, moist compress of centaury, wormwood, and St. John’s Wort. According to the Pharmacopoia Londinensis (1702), these ingredients all had hot and dry properties and cleansed and treated wounds. Centaury might be used to treat scurvy (often seen as a skin problem) or gout, while wormwood was thought useful in resisting putrefaction. St. John’s Wort was supposed to dissolve bad blood and cure wounds. The second remedy, an oil of turpentine with galbanum, was to relieve pain, soften the skin, and reduce the tumour.

By the time surgeon Ralph Calep saw Mrs Stevens in early 1698, her foot and leg were in a bad way: brown and withered with black spots and no feeling in the leg. She was in great pain and occasionally delirium, begging Calep for help. But the only solution Calep could think of was to remove the leg, which Mrs Stevens refused. Calep thought this was best since he “did not expect any Success in the performing of it”, given her age and weakness, and left “supposing I shou’d never see her more”. He advised her friends to continue the compresses.

A month later, Calep returned and was surprised to discover Mrs Stevens still alive, though with a hole in her leg that discharged black matter. Calep enlarged the opening to aid the flow. He also cut into a tumour on her knee, but was surprised to find nothing but air. He again left the patient, advising her to continue the compresses. When he returned another month later, he was not only surprised to find her still alive, but “to my admiration saw that, which thro’ the whole course of my Life I may never see again”: Nature had made a perfect separation of the mortified flesh, with the skin above looking healthy. At this point, he decided to remove the leg. Now, over ten years later, the woman was still alive! For Phil. Trans. readers, this would have indeed been a fascinating case—a peculiar physical problem, with a remedy that demonstrated the power of nature’s healing.

For the historian, the tale is intriguing for a couple other reasons. First: the surgeons’ claims to authority. Calep had one complaint after the amputation. He had hoped to take the leg for dissection, but “the Friends of the Woman deceived me”. They had promised to keep the leg for him, but then buried it in a secret location. Calep’s authority rested in his careful observation over time, as well as the verification of the story by Cowper. Cowper included a note to Sloane stating that he had also been to visit Mrs Stevens, though he had been unable to look at the thigh. Mrs Stevens was “decrepid” and the weather was too cold for her to show him. He did, however, feel the stump through her clothing and Cowper diagnosed her problem as one of petrification in the arteries. This problem, he had previously seen in “aged Persons” or cases of gangrene, and had published on it. Cowper’s authority rested in his reputation and previous scholarship.

But what is striking is the absence of real evidence: the amputated leg had disappeared and Cowper had not actually examined Mrs Stevens’ stump in detail. In the late seventeenth century, natural philosophers were establishing what counted as good evidence. Close observation and reputation were two of the crucial elements, but both surgeons recognised that their accounts would have been even more compelling if they had been able to examine the leg and stump. Each explained in detail why they had not done so.

The case is also interesting for what it tells us about the relationships among surgeon, patient, and patient’s friends. The “friends” (which would have included family) were important throughout, ensuring that Mrs Stevens received good care during her illness. Mrs Stevens also continued to have full control over her medical care, despite her occasional delirium. She refused the only treatment Calep could offer, amputation, until her leg started the process of separation itself. She was typical of many patients in this regard, who generally avoided surgery until it became the only option–unsurprising in an age without anaesthesia. Later, she also refused to show Cowper her stump in its entirety.

The patient’s control over the disposal of the body part appears to have been more contentious. Calep certainly wanted the leg for scientific purposes—at the very least for dissection, but possibly even intending to preserve it as a sample. He even seemed to expect that he should have it, suggesting that he’d been tricked out of having it when he called the friends deceitful. For Mrs Stevens, by contrast, there may have been some anxiety surrounding the leg’s dissection: what might happen to her body at the Resurrection? Was it shameful? By burying the leg, Mrs Stevens’ friends would have been acting on her wishes, or seeking to protect her.

A curious case, indeed, for contemporaries and historians alike!

By Chelsea Clark

Statue of Sir Hans Sloane in the Society of Apothecaries Physic Garden in Chelsea. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

The Sloane Correspondence is a rich source of information about gardening in the eighteenth century. The science of gardening at this time was a shared experience between friends and colleagues who traded specimens and cultivated their collections with great curiosity. Although gardens could be either privately or publicly managed, the collaborative aspect of gardening served many different purposes depending on the individual collectors or institutions involved.

English gardens were built for multiple purposes, from personal and private pleasure gardens to university organized and maintained medical gardens. Both the Chelsea Garden and several private upper class estate gardens during the latter half of the eighteenth century in Britain were a combination of these purposes. They were both aesthetic and practical, housing rare exotic treasures to display the owner’s status as well as contained local and distant medical botanicals for practical medicinal uses.

Apothecaries and physicians relied on many botanical remedies and thus needed access to gardens. This resulted in many of them becoming expert gardeners. According to a Parisian physician at the time, Jean Fernel, a competition between apothecaries and physicians inspired an invigorating cultivation of gardens with both common and acclimatized plants in order to maintain “dignity and authority” over the other.[1]

The Physic Garden, Chelsea: a plan view. Engraving by John Haynes, 1751. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

The Chelsea physic garden was originally property of the apothecaries of London, though it fell on hard times in the early eighteenth century. Physician, Sir Hans Sloane, become benefactor to the garden because he saw the value in the botanicals it provided and its potential to provide benefical botanical knowledge for the public. Sloane saw the importance of the garden for all types of medicinal use as well as for the maintenance and growth of botanical trading within England, Europe, and the newly acquired Colonies.

In 1722, Sloane leased a parcel of his land in Chelsea to the Company of Apothecaries of London on the condition that they maintain the garden for “physick” and send the Royal Society fifty specimens per year until 2000 specimens had been given.[2] The reason given for requiring the annual gift of specimens was to encourage the constant growth of the garden and to ensue it continued to be used for its proper purpose.[3]

French gardens were similarly split between public and scholarly gardens, however French gardens were steeped in state involvement with the promotion and running of gardens. The Jardin du Roi, established in 1640, was in name and function the garden of the French King, Louis XIV. It was also used by the Academie des Sciences for their exploration and acclimatization of botanicals and open to the public. The garden was maintained under state direction, as was the search and collecting of new specimens to fill the garden. It was managed as an economy that was “simultaneously social, financial and natural historical.”[4]

French botanical collecting was tied to their colonial expansion and French collectors were most interested in botanicals with economic value.[5] As a result of higher state involvement, French motivations were focused on economic gain rather than scientific curiosity; collecting and cataloging the world’s botanicals was less of a priority, resulting in the cultivation of different types of plants than in England, which centered on medicinal rather than economical specimens.

The discussions about gardens between Sloane and many of his British correspondents did not mention any state support or involvement. Their collecting appeared to be motivated by a desire to discover all the local and exotic species and where they were naturally found. As was the case for France, English collecting in its colonies did have an economic component; however, the perceived economic value of plants was not mentioned as the primary motivator of botanical collectors.

Without immediate state direction both personal and professional English gardens became significant players in the European exchange of botanicals. English private collectors and gardeners were successful at expanding their knowledge of species and contributing to scientific knowledge, while the French were successful at extracting economic value from their exploration of plants. Even though the French gardens were open to the public, the English exchange relationship between the personal collectors and the professional gardens allowed for information about botanicals to spread freely and the development of gardens across England. English gardens had perhaps less economic value than their French counterparts, but provided an abundance of natural history knowledge and practical medicinal value for its public.

[1] Harold Cook, Matters of Exchange New Haven: Yale University Press, (2007): 31.

[2] Isaac Rand, “A Catalogue of Fifty Plants Lately Presented to the Royal Society, by the Company of apothecaries of London ; Pursuant to the Direction of Sir Hans Sloane, Bart. Bresident of the College of Physicians and Vice President of the Royal Society,” Philosophical Transactions, 32 (1722).

[3] Ruth Stungo, “The Royal specimens From the Chelsea Physic Garden, 1722-1799,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 47, no. 2 (July 1993): 213.

[4] E. C. Spary, Utopia’s Garden Chicago: Chicago University Press, (2000): 51.

[5] Spary, “ “Peaches which the Patriarchs Lacked”: Natural History, Natural Resources, and the Natural Economy in France,” History of the Political Economy 35, 2003: 14-41.

A long-standing myth about epilepsy is that it is tied to the lunar cycle, worsening during the full moon. Just Google it to see what comes up in the search… But the boundary between what we see as myth and what eighteenth-century people saw as medicine is blurry, as a quick search of the Sloane Correspondence database for epilepsy shows.

A man suffering from mental illness or epilepsy is held up in front of an altar on which is a reliquary with the face of Christ, several crippled men are also at the altar in the hope of a miracle cure. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

In February 1739, physician Christopher Packe consulted with Sir Hans Sloane about Mr Roberts’ recent epileptic fit (BL Sl. MS 4076, f. 220). Before describing the fit, Packe specified that it occurred on the morning of the full moon. Before the fit, the patient appeared wild and suffered from a numb leg and a swollen nose. In the hopes of preventing a seizure, Packe prescribed a vomit. Mr Roberts, moreover, had been diligent in following Sloane’s orders: a restricted diet and various medicines. Everything was being done that could be done, to no avail, and Packe was “apprehensive” of the next full moon.

An undated, unsigned letter came from a gentleman aged 28, who had been “seized with epilepsy two months ago” after having no fits between the ages of 16 to 20 (BL Sl. MS 4078, f. 329). Epilepsy ran in his family, he reported, with his mother being “subject to it or at least violent hysterick disorders from girlhood” and his father having seizures for several years before death. The patient wondered if the trigger had been his change from winter clothes to spring clothes, as well as drinking more than usual for several weeks prior to the recurrence. The timing of his changed lifestyle could not have been worse, since “about three days before the full moon immediately preceeding the Vernal equinox he fell into that fitt”.

The focus of these letters on full moons and clothing changes may seem superstitious to us today—and the parallel between epilepsy and hysteria perplexing—but reflected the wider medical understanding of the time. Botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (with whom Sloane studied in France) and physician Thomas Sydenham (with whom Sloane worked in England) considered hysteria and epilepsy to be related: convulsive disorders that affected the brain.[1] According to contemporary treatises, other related ailments included vertigo, palsy, melancholy, fainting, and rabies.[2]

Well-known physicians Thomas Willis (1621-1675), Richard Mead (1673-1754) and John Andree (1699-1785) discussed some of the old stories about epilepsy. Willis and Andree noted that epileptic fits were so shocking to observers that they had, in previous times, been attributed to demons, gods or witchcraft.[3] Willis’s remedies may appear just as magical to modern eyes, but they would have been common in early modern medicine. There was also a key difference: he treated epilepsy as natural rather than supernatural. Willis began his treatments with a careful regime of vomits, purges, and blood-letting to prepare the body for preventative remedies. These included concoctions of male peony, mistletoe, rue, castor, elk claws, human skull, frog liver, wolf liver, amber, coral (and so much more), which would help in tightening the pores of the brain. Some of the medicines were also to be worn on the body rather than ingested, perhaps a silk bag (elk hoof, mistletoe and peony roots) at the waist or an elder stalk amulet at the neck.[4]

By the time Andree was writing, some of Willis’ seemingly magical recommendations had been lost, although most of the remedies remained the same. Andree, however, looked beyond the brain for the source of the problem. He emphasised that it was important to identify the underlying cause of the epilepsy: humoral obstruction, plethora of blood, head injury, worms or fever.[5]

The moon continued to be important in Mead’s and Andree’s understanding of epilepsy. Mead argued that the human body was intimately affected by the influence of the sun and moon, with epilepsy and hysteria being particularly subject to lunar periods. The most critical of these were the new or full moons around the vernal and autumnal equinox, moments of important change. Mead was particularly interested in periodicity within the human body, which included periodical hemorrhages (including menstruation). Using the same rationale for explaining men’s periodical hemorrhages, Mead seemed to suggest that weak or plethoric (too much blood) bodies were particularly subject to the lunar cycle.[6]

Andree took the effects of the moon on epilepsy as a given, recommending that epileptic patients be given vomits around that time. He focused on the necessity of regulating the body through good management to prevent weakness and plethora. Drunkenness and gluttony, erratic emotions or sudden frights, overuse of opiates, excessive sexual intercourse could all trigger epilepsy. Puberty, with its rapid changes to the body, was a dangerous time when epilepsy might go away altogether, or worsen. Epilepsy that did not go away was thought to result in gradual degeneration—stupidity, melancholy, palsy, cachexia (weakness)—that would be difficult to treat.[7]

No wonder Sloane’s patients were so worried! For Dr Packe, Mr Roberts’ condition would have appeared to be deteriorating, in spite of the best efforts of doctor and patient. And the unnamed gentleman, given his family’s medical history, must have blamed himself for making potentially disastrous choices at one of the worst times of year. Timing was everything when it came to epilepsy. In Sloane’s lifetime, many old ideas about epilepsy had been relegated into the realm of myth, but a connection between the full moon and epilepsy remained as firm as ever.

[1] Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, Materia medica; or, a description of simple medicines generally used in physick (1716), pp. 84, 265; Thomas Sydenham, Dr. Sydenham’s compleat method of curing almost all diseases, and description of their symptoms (1724), p. 150.

[2] See, for examples, Richard Mead, Of the power and influence of the sun and moon on humane bodies (1712); John Andree, Cases of the epilepsy, Hysteric Fits, and St. Vitus Dance, & the process of cure (1746); Thomas Willis, An essay of the pathology of the brain and nervous stock in which convulsive diseases are treated of, 2nd edition (1684).

[3] Willis, p. 11; Andree, p. 7.

[4] Willis, pp. 18-20.

[5] Andree, pp. 3, 10-12.

[6] Mead, pp. 31-42.

[7] Andree, pp. 10-12, 25.

A map of “Terra Australis” by Jan Janssonius (1657). Credit: Wikimedia Commons. Uploaded by: Joop Rotte.

By Matthew De Cloedt

In early December 1721 James Brydges, the first Duke of Chandos, requested a meeting with Sir Hans Sloane. Brydges, a shareholder in chartered companies operating in New York, Mississippi, and Nova Scotia, wished to gain Sloane’s scientific expertise and advise an expedition of the Royal African Company headed by a “good Botanist” named Mr Hay. Brydges sent Francis Lynn, the company secretary, to Sloane’s residence three days later to answer his questions regarding the venture and to inform him of “the Nature of Drugs, plants, and spices” they were expecting to gather on the expedition.

Though the Royal African Company had lost its trading monopoly after the Glorious Revolution it continued to receive support from prominent individuals. Men like Brydges bet on its success, for the potential financial losses were negligible compared to the possible returns should a profitable, new commodity be discovered. Sloane was a natural choice for Brydges. He was wealthy thanks to his Jamaican interests, well connected to global trade networks, aware of the riches to be gained from botanical commerce, and friendly with the family of Brydges’s wife Cassandra Willughby. Sloane obliged Brydges’ request and directed company officials in Whydah to collect particular plant specimens. [1]

Sloane regularly received invitations to lend his scientific expertise or invest in business ventures. When he supported a person or company he connected them to a network that included the royal family and contacts around the world. Rejected proposals ended up in his large collection of manuscripts. Some of the more interesting schemes point to what might have been had Sloane seriously backed their proponents.

In the spring of 1716, shortly after he was created baronet, Sloane received a letter from Woodes Rogers asking for all the information he had on Madagascar. The Royal African Company had excluded individual traders from the West African coast, driving them to East African trade centres. English attempts had been made throughout the seventeenth century to establish meaningful trade in Madagascar, which was dominated by the Portuguese and Dutch, but they had little success. Rogers was determined to break into this market.

Rogers had already been a Colonial Governor and privateer in the Bahamas, but wanted to take on a more ambitious project in starting his own colony on Madagascar. There is no evidence that Sloane even replied, but his large library, reputation as a traveler and natural historian, and place within the scientific community attracted Rogers. It would not have been the first time Sloane helped a pirate.

John Welbe wrote several months after Rogers to request Sloane’s assistance. Welbe was in prison for a debt he failed to repay and promised to undertake a voyage to “Terra Australis Incognita” if Sloane helped him. Welbe had long been seeking a patron to support his voyage and forwarded a petition he had written to the Crown of Denmark as evidence. That Sloane was apparently Welbe’s second choice after the Danes indicates how great a patron he was considered to be, or how desperate Welbe was to be freed from bondage.

The unknown territory had been spotted before, but no serious attempt at settling there had been made. With Sloane’s help, Welbe might have gained the support of others with financial and/or natural historical interests in what became Australia, but nothing came of the plan. There is no evidence Sloane bailed Welbe out of prison or even replied to his letter, but in any case he did not sponsor any voyage to the “Terra Australis Incognita”. It would take another prominent Royal Society member, Joseph Banks, to really put Australia on the map.

With his busy medical practice and duties to the government, Royal Society, and Royal College of Physicians, Sloane was too busy to deal with all of the schemes proposed to him. But the map of the world by 1720 might have looked different if Sloane had chosen to throw the weight of the Royal Society and his social network behind Welbe or Rogers.

Counterfactuals aside, Sloane was an ideal patron for international scientific and commercial expeditions, for he had first hand experience. When he traveled to Jamaica in 1687 he was, like Mr Hay, a “good Botanist” trying to make a name for himself using science, commerce, and foreign travel as the foundation for a successful career. Understanding why Sloane ignored Welbe and Rogers might be simple. The two did acknowledge Sloane’s scientific expertise, but focused on securing his financial support. Sloane was not afraid of making money, but he was equally as interested in the opportunity to contribute to science through exploration and commerce. Appealing to this desire might have been the best approach.

[1] Larry Stewart, “The Edge of Utility: Slaves and Smallpox in the Early Eighteenth Century”, Medical History 29 (1985), 60-61.

Patrick Blair, Sloane MS 4040, f. 169r.

Dundee May 24th

1706

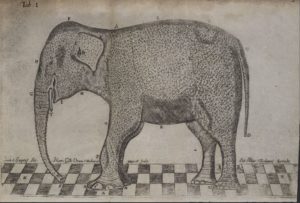

Sir Yours of the 9th Instant is so obliging, & you have therin exprest such a Concern for the Papers I presum’d to trouble you with; that there only now remains in me a deep & grateful Sentment of such Surprising Kindness, & a despair of ever being able to give you any requital. All I can say, is, that since the Papers are now Safely in your hands, you may do with them what you please; for I Account it my greatest happiness, that Dr Sloane likes them very well. It would be no less my earnest wish, than your desire to acquaint you with such small Improvements as I can make in the discovery of any thing relateing to natural History. And if any enquiry I shall be able to make by a Late case of Providence, (I shall call it Lucky, if it shall any ways tend to that satisfying you or your honourable Society’s curiosity) may be worth your while it shall be my greatest ambition to acquaint you therwith. The Elephant which Lately travers’d the most of Europe; hapned upon the 26th of the ^last^ month to fall down & Expire within a mile of this place; I know not whether I more regreated its dying in the open fields, (since because of bigness it could not be transported) where the great throng, the heat of the day, small assistance, & Last day of the week, which kept me from doing all; that day, or leaving any thing undone till to Morrow; wherby such curious enquiries as might have been made into its Viscera were altogether Lost, or rejoice in being so near it, as I could not miss to observe Something, tho not in the Softer, yet in harder parts, any the Bones, of which I intend to mount a Sceleton, which with the Skin already So stuff’d, that it represents the Animal to the life: will be none of the meanest Rarities in Europe. I desire an exact Description of the Bones, but whether it shall ever see the Light, tis only you must determine eno, for if other Pens have been dipt upon that Subject my weake endeavours will readily prove less usefull. And as the kindness you have shewn me, makes me hope for your Patronage; so the steps I make therin can be only advanc’d by your encouragement. My Mehtod of Pro= cedure shall be 1. To take an exact account of their dimenstions & Weight 2. To ob= serve their Situation, Figure, Connexion &c 3. To lay down Rules for mounting the Sceleton & 4. To express all in Taille doux, but all depends upon your honouring me with a Return, which I wish may be with the first conveniency.

Patrick Blair, Sloane MS 4040, f. 170r.

Sir

Your most Sincererly devouted humble se.

Patrick Blair

Some days ago I gave a short Account of my Observations when I open’d the Elephant. to our good Friend Dr Preston (who has now got the Physick Garden at Edinburgh) for they were so coarse; that I durst not presume to acquaint you with them Since writing of this he has desir’d a further Account of me especially concerning the Trunk & its Structure, which I intend to give him within a few days. He writes me that he is resolv’d to acquaint you with it therefore when it shall come to your hands, I beg to excuse the Imperfections, for though I may use my utmost endeavour, yet the inconveneances I labour’d under cannot but make it very lame.

Fig. 1 from “Osteographia Elephantina”.

Fig. 2 from “Osteographia Elephantina”.

Blair’s account of the elephant bones was published in two parts in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society:

“Osteographia Elephantina”, Phil. Trans. 27, 326 (1710): https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1710.0008 .

“A continuation of the osteographia elephantina”, Phil. Trans. 27, 327 (1710): https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1710.0009 .

The envelope has a red seal and two post marks, as well as a note ‘pd’.

By James Hawkes

Saving lives may have been Sir Hans Sloane’s day job as a physician, but in one case he even saved a friend from the hangman: Patrick Blair, who had been sentenced to death for high treason.

A Scottish surgeon and botanist, Blair had known Sloane since 1705 after persuading a fellow Scotsmen to introduce him. Sloane and Blair corresponded for several years on diverse subjects, from botany, elephants, medical practices, books and more. But in the aftermath of the failed Jacobite rising of 1715, Blair also discovered the real importance of networking and patronage.

Britain was in a state of political upheaval for decades following the Glorious Revolution of 1688. James II may have been dethroned, but his followers–Jacobites–repeatedly attempted to restore him to the throne. The Union of the English and Scottish parliaments in 1707 was resented by many in Scotland and strengthened Jacobitism.

Sloane, born a Presbyterian son of Ulster planters, was staunch Whig and loyal to the new royal family. Not only was his brother, James, a Whig Member of Parliament, but Sir Hans was a royal physician. In 1714, he had even attended Queen Anne upon her deathbed, prolonging her life long enough to thwart the schemes for a Jacobite restoration and to secure the Protestant Hanoverian succession.

Just one year later came ‘the Fifteen,’ a poorly organised Jacobite uprising in both Scotland and western England. Blair joined the revolt in Scotland as a surgeon, but was captured at the Battle of Preston and sent to Newgate Prison, London. He desperately wrote to his friends in the hopes of obtaining relief for himself and his suffering family.

my poor wife and children are in greatest misery and distress and that the very little they have to Live upon in Life to be utterly Lost so that they are Like to be reduced to a starving condition unless the Government shall see fit to show me their mercy and grant me relief.

In these pathetic pleas Blair also denies that he was ever truly a Jacobite, insisting that the rebels gave him no choice. One might suspect that Sloane found these claims a little hard to swallow given that he probably knew that Blair came from a Jacobite family and was religiously a Non-Juror–a member of the schismatic Episcopalian church who refused to swear allegiance to any but the exiled Stuarts.

It is only natural that Blair sought to preserve a sense of normality during this time of personal crisis. For instance, he sent Sloane a letter discussing their mutual botanical interests and his desire to do some gardening for Sloane, “I want to be serviceable to you for the obligations I received from you. The plants spring in my mind as fast as they do in the ground you proposed I might assist you with Last.”

Despite the efforts of his friends, including Sloane who visited him in prison, Blair was condemned to death following his guilty plea. He continued to beg for Sloane’s help.

But now having in the most submissive manner subjected myself to his majesty’s mercy I hope by your intercession… to obtain his most gracious pardon and Liberation … I therefore humbly crave you’l be pleasd to use your endeavours in that matter.

Blair had good reason to be frightened, as the Lord High Steward’s sentence of death against other rebels a few months earlier declared that they were to be brought from the Tower and:

drawn to the place of execution. When you come there, you must be hanged by the neck, but not until you are dead; for you must be cut down alive, then your bowels must be taken out and burnt before your faces; then your head s must be severed from your bodies and your bodies divided each into four quarters and these must be at the king’s disposal.[1]

Although most of the condemned had their sentences commuted to a ‘mere’ beheading, it’s unlikely that Blair would have been reassured. There was a distinct possibility that he could end up one of the relatively few Jacobites made an example of, either through execution or exile to the colonies. Although Blair hoped that Sloane could secure him a pardon, the government kept him waiting until midnight before his scheduled execution to inform him of his reprieve.

Afterwards, Sloane continued to support Blair financially by helping him to relocate and put his life back together. This demonstrated not only the enduring value of wealthy and well-connected friends, but also how friendship could cross political and sectarian boundaries. Despite the polarised and often violent atmosphere of politics in this period, friendship and the higher cause of the Royal Society and Republic of Letters still trumped politics.

Broadside image of the Pretender, Prince James, Landing at Peterhead on 2 January 1716. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, aside from simple friendship, cultivating these connections may have represented something of an insurance policy for Sloane, just in case the King over the Waters should ever follow in footsteps of his uncle Charles II and make a triumphant march into London.

[1] Margaret Sankey, Jacobite Prisoners of the 1715 Rebellion: Preventing and Punishing Insurrection in Early Hanoverian Britain, (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2005), 27.

[fol. 198] Rome 7 July 1728 Sir I take ye liberty to adress you this packet for Dr. William Derham being ye observations of Monsigr Bianchini upon ye Jovial Satellites, which I reckon may be usefull unto ye Society, & consequently will bear the charge of its postage otherwise I would not be so indiscreet. The severall papers sent by sea for me are not yett arrived at Leghorne, & I wish these I have sent over the same way for ye use of ye society may have had a quicker passage. The Accademie of ye Instituto of Bologna, & the Professours of Padoua [sic] discover every day more upon examination the mistakes of Rizzetti about ye Opticks of Sr Isaac Newton, so that Vallisneri writes me about him, anche in questo modo si deventa famoro, & thus he is upon sending my two copys of his last printed works to be sent over by me to G. Britain, one for ye R.S. & another for you, whereof you shall in due time be informed, & Monsig. Bianchini will give me his new mapp of ye Globe of Venus as soone as he has an account the K. of Portugal has received his, to whom he has dedicated it, so if I can, I will send all together to ye R.S. You will have received the answers from the Professours of Padua which I sent to our President for you, & having at present no litteraire news to impart to you I Remaine Sir Your very humble servt Thomas Dereham

Sir Thomas Dereham (c. 1678-1739) was a British expatriate and Roman Catholic who lived in Italy. He had a close association with the Royal Society (https://collections.royalsociety.org/DServe.exe?dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqCmd=Show.tcl&dsqDb=Persons&dsqPos=0&dsqSearch=%28Surname%3D%27dereham%27%29).

[fol. 187] Rome 12 June 1728 Sir Your favour of ye 26 Aprill is just come to my hands, for which I return you many thanks, as for having communicated the contents of mine unto the R. Society & acquainting me with there having taken it very well & for having sent me the late Transactions, & Sr Isaac Newtons Cronology, an abstract whereof has been only seen in these parts, & putt every body in great expectation, therefore I which that Mr. Green keeps his word with you in forwarding them soone to me, & takes the like care in our future correspondence. The Observations on Venus, & the domus Aureal Neronis by Monsgr Bianchini are both under the press, & his nicety is the occasion of the delay. Here enclosed are the answers of the Professors of Padua to Dr. Rutty, which I entreat you to forward to him, & to tell Mr. Derham that Monsigr Bianchini makes me hope to receive of him soon his Observations on ye Jovial Satellites which I shall send him without loss of time & return the answer I owe unto him. I expect with great impatience the efect of your proposing Dr. James Beccari of Bologna to be Member of ye Society who every day more deserves such a distinction, being one of those that actually in ye Instituto of that Town trieth over again the Optical Experiments of Sr Isaac Newton to confute Rizzetti, & I am informed they all answer exactly, & prove more & more the ingenuity of the first Author. I am with the greatest esteem, & sincerity Your most Obedient, & most humble servant Thomas Dereham

Sir Thomas Dereham (c. 1678-1739) was a British expatriate and Roman Catholic who lived in Italy. He had a close association with the Royal Society (https://collections.royalsociety.org/DServe.exe?dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqCmd=Show.tcl&dsqDb=Persons&dsqPos=0&dsqSearch=%28Surname%3D%27dereham%27%29).

Morton thanks Sloane for his favours and for his ‘favourable representations of me, and my poor collection, to the Royal Society’. He will do his best to honour them. Morton is busy describing ‘Fossil Teeth and Bones’ and would like to speak about them with a particular member of the Royal Society. He believes a specimen he examined previously is ‘the Grinder of an Elephant’ and would appreciate the opportunity to confirm that opinion. Morton asks Sloane to send the latest Philosophical Transactions. He promises to pay for them. He has more questions on ‘Books & Curiosities’, but does not want to burden Sloane any further. John Morton was a naturalist who was in correspondence with Sloane from roughly 1703 to 1716. Morton contributed nearly one thousand specimens (fossils, shells, bones, teeth, minerals, rocks, man-made artifacts, etc.) to Sloane’s collection (Yolanda Foote, Morton, John (16711726), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2010 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/19364, accessed 2 July 2013]).