Henry Barham Sr. to Hans Sloane – July 3, 1725

Item info

Date: July 3, 1725 Author: Henry Barham Sr. Recipient: Hans SloaneLibrary: British Library, London Manuscript: Sloane MS 4048 Folio: ff. 15-16

-

Language

English

-

Library

British Library, London

-

Categories

Government, Legal, Medical, Scholarship, Scientific

-

Subjects

Botany, Jamaica, Medicines, Natural History, Plants, Worms

-

Date (as written)

July 3, 1725

-

Standardised date

-

Origin (as written)

Jamaica

-

Others mentioned

Draughtsman Robert Pool

-

Patients mentioned

Original Page

Transcription

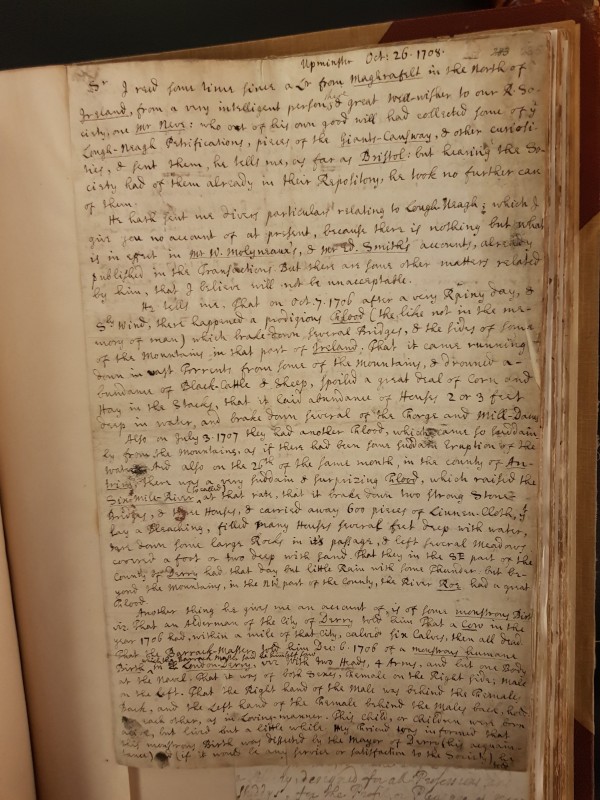

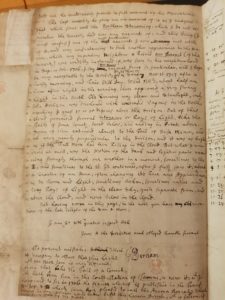

[fol. 15] Jamaica July 3d 1725 Worthy Sr Your Kindes Letter of October I Did not Receive until March Last Wherein you friendly Admonish me of my mistakes in My Hortus: for wch I Give Hearty thanks: knowing that no Man is a Fitter Judge and to Correct than your Self wch I hope you Will if you think it (after your amendments wch I hope you Will do me that Favor) and after your 2d Volume is out: Worth Printing and any Bookseller Will venture Upon the undertakeing they may have it only letting of me have bory [?] of them myself I know it Will Sell in Jamaica for most Planters are in great Expectation of it but if not Worth Printing or nobody Will undertake it I Desire it may be Sent to me again I Long to See yr 2d Volume that Sort of Apocynum Called Blood Flower is Now Much in use here and ther Planters Will not be persuaded that it is not the True Ipecuana They Now Frequently give the Juice of the Stalk and Leaves even to Children for Worms wch they affirm is Never Fails to bring them a Way they Own it Works upwards and Downwards but that without any prejudice or Dainger as for my part I Never Dare be So Bold as to Administer it But as I Mentioned to you before I have stopt Old Gleets with a Week Decoction of the Leaves and Since my last arrival I have Orderd a Tea to be made of the Dry Flowers to those that have Laboured under Old Continual Gleets without Malignancy or Verulency it hath perfectly Cured them and those that were in Old Age I Should be proud to Serve you in Sending you Specimens of Plants Altho I think I Can ad butt Little to what you have done But I Grow Old and very Corpulent being much Fatter than when I was in England: I keeping no Horse and Seldom or ever Ride into the Country; have not the Oportunity to Collect any Plants and if I Imploy any Person to gett them they lay them down in Such a Rude manner that its Difficult to Distinguish them as I Believe you found it So by the Logwood Branch I Sent you by my Son wch Grows Now in Great Plenty in Jamaica and the Planters make great use of them for Fences Growing very Thick Always Green and very full of Sharp Prickle when young I have mett with an Ingenious young man who Draws and Paints very Nicely who I have Instructed is the Knowledg of our Plants. He hath undertook to put the True and Living Colours of some of yours Cutts with their Flowers; This Person is now in the Mountains when He Returns I Shall Imploy Him to Gett Some of the Gaudiralla Bitter Fol. 16 Bitter Wood and the 2 Sorts of Brasilotto or any thing Else you Desire: As to my Sallary its Opinion of the Best of our Lawyers I must beg in the Suit there and if you are in my Favours wch they all say it must according to Equity Justice it Will Soon be Obtained Here but if Judgment be Given for me here its Difficulty to Gett the Mony: for Altho Mait [?] Ayscough hath Carried a Rich Widdow She Can have but her Thirds She having many Children and his Own Estate is Mortgaged for more than its Worth to his Brothers Widdow in England. And there is no touching his Body being Chief Justice and Presedent of the Council young Long Pleads Nonage [?] and his Curcumstances very Low sold his House lately for 800 pounds wch is Worth above 1200 wch bespakes his Necessity the Commission […] over: by Bad Wheather and Neglegence together the Time for Executeing was Elapsd the Patented Commissioners took the Advantage of it therefore forced to Send over for an Alias Commission Since that one of the Subscribers Commissioner is Dead on Robert Pool So that I Believe little Will be made of it: I was Ready with all Matters Relateing to the Affair: wch Would have been of Great Service to the Subscribers; but if they make No steps to Consider me. I Shall forget them and if I Can have no Satisfaction from the Patenters I must endeavour to be Contented: wch is all at Present wishing you health, Joy and Prosperity: I always Remain yr Most Humble Servant H Barham

Henry Barham (1670?-1726) was a botanist. He lived in Jamaica and corresponded with Sloane on the plant and animal life of the island. Parts of Barham’s letters to Sloane appeared in the latter’s Natural History of Jamaica (T. F. Henderson, Barham, Henry (1670?1726), rev. Anita McConnell, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1374, accessed 13 June 2011]).

Patient Details

-

Patient info

Name: N/A

Gender:

Age: -

Description

-

Diagnosis

-

Treatment

Previous Treatment:

Ongoing Treatment:

Response: -

More information

-

Medical problem reference