Things I learned on the weekend… Slacker dads watch sports instead of read their children stories. They avoid housework and childcare as much as possible. They prefer work-life to domesticity. And above all, they look upon “Wet Wipe” daddies—those who are prepared with things like spare nappies and who concentrate on what their children are doing—with contempt. Or so claims Alex Bilmes, editor of Esquire, who shared his “Confessions of a slacker dad” in The Guardian. Bilmes wonders when being a good father became so complicated, concluding that “[t]he expectations of fathers have changed. More is demanded of us.” Righto. And off he went at speed, riding on his false assumptions about fatherhood in the past!

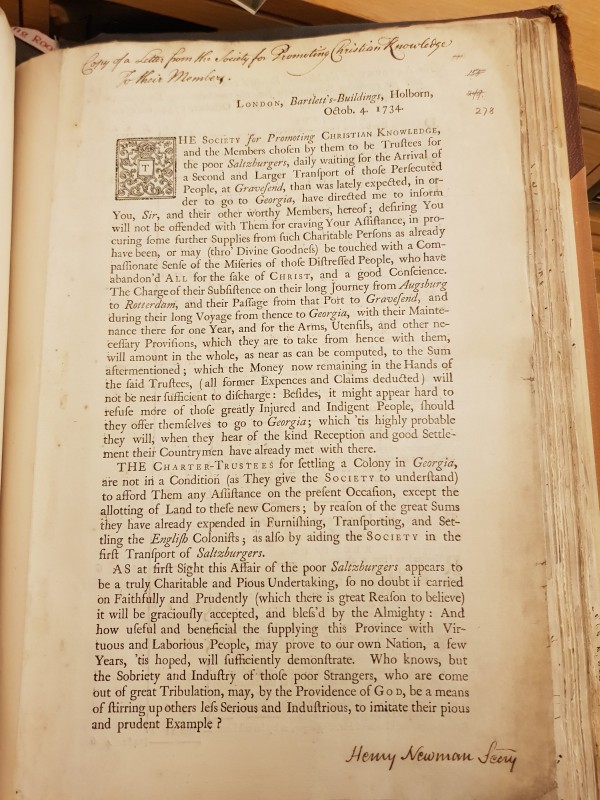

A father feeding his infant whilst the mother attends to domestic jobs and a small child plays with its food. Etching after A. van Ostade, 1648. Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Joanne Bailey, author of the excellent Parenting in England 1760-1830, certainly has much to say on the complexities of fatherhood, identity and parent-child relationships. Being a dad was not, historically, exactly a walk in the park (with or without a Scandinavian buggy). As Bailey points out in one of her blog posts, Georgian fathers experienced (and were expected to experience) a profound range of postive and negative emotions.

In another post, she explains that Georgian society expected men as well as women to be emotional beings, resulting in an ideal that fathers should be “tender” or “nursing” or—to use a modern term–“involved”. Victorian and mid-twentieth century fatherhood, by contrast, emphasised less emotional expression (particularly in men), shifting the cultural focus to fathers’ roles as breadwinners.

The anti-Wet Wipe father Bilmes would, I expect, be surprised by (what I now call) the Medicinal Plaister Papas of the early eighteenth century: the men who performed a wide range of caregiving roles within the household, including nursing and remedy preparation. The Sloane Correspondence is filled with concerned fathers who oversaw the health care of their children.

Many fathers provided detailed reports of their children’s health and administered treatments. In a letter dated 1 February 1697, John Ray grieved for his daughter who had died of an apoplectic fit after three days of delirium. He blamed himself for giving her one of his own remedies, only to see it fail on this crucial occasion.

William Derham was concerned about his “little daughter”, aged nine, on 3 November 1710. She had been “seized immediately with a great suffocation like to have carried her off divers times”. Derham reported his daughter’s symptoms (sore throat and lungs, heart palpitations and blindness) and described her treatments, including the use of a microscope to examine her eyes. It is possible that a local physician had undertaken the microscopic examination, as the language is ambiguous. But knowing Derham’s scientific interests, it seems more likely that Derham examined his daughter’s eyes himself.

Others were concerned that their own sins might be visited upon their offspring with terrible consequences. Edward Davies, on 8 July 1728, was worried that his son’s joint pain might affect his head. In addition to reading up on John Colbatch’s remedy for convulsive distempters ( A Dissertation Concerning Mistletoe, 1723), Davies had treated his son with Daffy’s Elixir. Davies had two main questions. First, he wondered if his own past mercury treatments (for venereal disease?) had caused his son’s ill health: “my blood was poyson’d in my youth with a Quicksilver-gird & I wish my off-spring do not suffer that”. Second, he was also unsure whether teaching his son Latin to prepare him for public school would do him more harm than good in his condition. Raising a child was a fraught venture, from passing on one’s own health problems to training them well for the future. In any case, Davies was deeply involved in his son’s upbringing.

Fathers also exchanged useful medical knowledge. In August 1723, Mr. Townshend wrote to Sloane that his daughter Ann had been on her way to visit Sloane about her blindness, but Townshend had such trouble parting with her that she would be “14 days longer”—and he would have preferred it if Sloane could come to Exeter! A month later, Townshend expressed his gratitude for Sloane’s help, although Ann was no better. Townshend had, nonetheless, suggested that Mr. Farrington and others contact Sloane for assistance.

Sure enough, that same day, Mr. Farrington had written to Sloane about his daughter’s eye problems. Farrington noted that when his daughter (now 21) was ten, she’d suffered from such violent head pain that she was expected to die. She eventually lost sight in both her eyes and although she was able to move around the home and gardens, she was unable to travel beyond them. Farrington described the nature of her limited sight, as well as the treatments and diagnosis that she had received. By the next month, Farrington waivered between hope and despair based on Sloane’s (unknown) response, but he sent Lady Yonge to collect Sloane’s remedies. As of 23 November 1723, Farrington noted that Sloane’s treatments seemed to be working “and the load she hath had above the eyes taken off”.

These last two cases reveal two worried fathers, both of whom were familiar with the details of their daughters’ treatments. Townshend’s recommendation of Sloane’s assistance to his friends also suggests a network of fathers who exchanged medical knowledge—in the case of Townshend and Farrington, about their daughters’ shared problem.

Distant dads? Not at all! These early eighteenth-century Medicinal Plaister Papas who wrote to Sloane had far more in common with the modern Wet Wipe fathers than Bilmes and his Slacker Dad ilk.