Thomas Harward to Hans Sloane – June 16, 1731

Item info

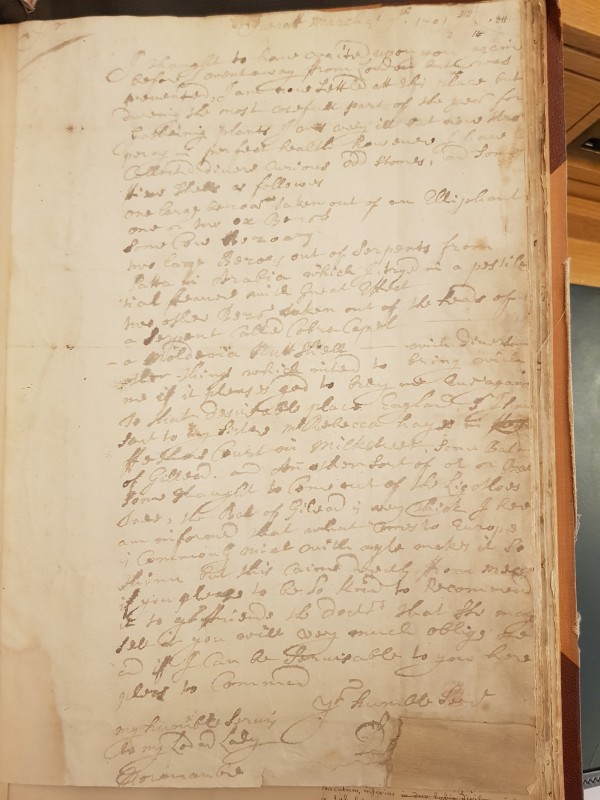

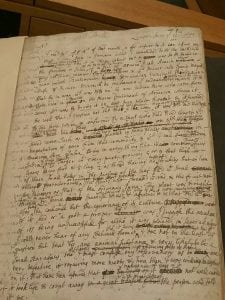

Date: June 16, 1731 Author: Thomas Harward Recipient: Hans SloaneLibrary: British Library, London Manuscript: Sloane MS 4051 Folio: ff. 255-256

-

Language

English

-

Library

British Library, London

-

Categories

Curiosity Reports, Government, Medical, Scholarship, Scientific, Trade or Commodities, Travel

-

Subjects

Amber, America, Bioprospecting, Botany, Diseases, Fish, Inoculation, Medicines, New England, Oils, Smallpox, Snakes, Whales

-

Date (as written)

June 16, 1731

-

Standardised date

-

Origin (as written)

Boston

-

Others mentioned

-

Patients mentioned

Original Page

Transcription

[fol. 255] Boston June 16th 1731. My most honourd Friend After a very long, & dangerous voyage, by ye Good Providence of God, we landed at ye Port of Boston, ye 13th of November last, a little before night, & were received wth Great Civilities by ye Inhabitants of ye Town. Our Winter here has been very severe, & tedious, much colder than in old England, & our spring scarce perceivable till ye Beginning of May. I have taken some Pains to see a little of this Country for abt three weeks past, & intend to see More before ye summer is over. Here are many Things in these Parts, yt deserve ye Notice of ye Curious, not only in the vegetable, but ye Animal Kingdom. About 8 Days ago I had two Captains at Dinner wth Me, who came from ye Island of Nantucket, wch Place is remarkable for ye sperma ceti whales. And these two Men are ye most famous in all those Parts for catching these, as well as the common whales. Tis these Gentlemen yt supply us wth sperma Ceti, & Amber grease, to a large quantity some Years: And I shall putt them in a way of making it as pure, & white, as any you have from Holland, or any othr parts whatever. Concerning these two Medicines I received ye following account from them, wch I humbly conceive is more perfect, & clean than any Notices you have yet had of these two valuable Druggs. They assure me yt all ye sperma Ceti they have ever gotten, is taken directly out of ye Head of ye particular kind of whale, wch They call ye sperma Ceti Whale, in Distinction from ye othr. And they tell me farthr, yt it is not of an Oily Nature, as some have given out, but rathr of a Marrowy substance, like ye Brain of othr Animals, yt the two ventricles of ye Head are full of it, only parted by some Membrane, yt it must be ye real Brain, there being Nothing to be found in these Cavities besides: wch to me is a Demonstration. And as to ye Amber grease, They declare they allways find it in the Rectum of ye same Whale, near ye Fundamenti, & no where else. yt all the excrement of ye Whale, in the othr Intestines, has exactly ye same smell, tho much Thinner than in ye Rectum. & more of an oily nature; and they believe by evaporation, &c it may be brought to ye same Consistencey wch they have promised the Me to try ye very first Opportunity. That they often discharge this Amber Grease, as excrement, when wounded, & in Pain, like to othr Animals, wch is a Considerable Losse to them, for it usually sinks at first, till it comes to be more inspissated, & hardend in ye water wch will soon raise it to ye surface, & so it will continue floating, till it be driven on some Rocks, or Tossd upon some stone. Besides they often lose those whales after they have wounded them, & yt Mortally, And as soon as they are torn in Peeces, or corrupted in the sea, The Amber grease will be set at Liberty, & immediately be floating till lodged at Last some where, according as ye Current Happens. And this I take to be a Good Reason, why Amber grease is so often found upon ye Rocks, & on ye shores. The first they ever found in the Rectum of this kind of whale, wch they call ye arse gutt, so as to take notice of it, near this Island, was in the year 1721. And they lookd upon it as Excrement, And threw half of it into, ye sea, & was going to throw ye Rest, wch was near hald an hundred weights, but luckily prevent by a Person in the vessel, who had seen some Amber grease before at ye Bahama Islands, & so prevaild on them to save it. I intend very soon to try some Experiments on our Rattle snakes, wch are very rife in these Parts. And I make no Doubt at all, but yt their adops, or oil, if properly prepared, is as Good, & sure an Antidote agst their poisonous Bite, as ye adops viperanum is for the one Thing I know; yt it does better (I mean their Flash) in ye Thoria Androm. & is an higher alexipharmic, than ye flesh of vipers. Here is an Apothecary yt has used their Flesh in ye Thoriaca for some years, & I have ordered ye same Thoiaca wth very good success. Here are many curious Plants, & othr Rarities in this new world, yt have escaped all observation Hitherto, and if my circumstances woud allow me, I shud spend more Time, & be more exact, & Curious in my Enquiries abt them. But my Docket will not give Leave. Doctr Baylston is living Here, I have but small Acquaintance wth Him, He is a rattling sort of spark, & but of small esteem among ye better sort. Doctr Willm Duglass who wrote a small Treatise upon Inoculation, & a practical Essay on ye small pox, wch I suppose you have seen, is a very Ingenious man, & my very Worthy Friend. We have a famous Negroe Doctr in Virginia, who after Doctr Blair, & Doctr Nichols had made some tryals of ye success of his Medicines, & found to answer, the Assembly there set Him free, & settled 20 pds per Ann on Him for Life to communicate his Arcanum, for ye Grand Pox, & ye yaws, wch is the Hereditary Pox. The Decoction is as follows, of Spanish Oak Bark 2 parts [fol. 256] of ye inner Bark of ye White Pine 1 part & of ye Bark of ye Sumach Root 1 part in Common Water. One Pint is to be drank warm, and half a Pint cold immediately after, wch will soon cause vomiting. Then half a Pint is to be drank morning, noon, & night, daily untill ye cure is perform’d, wch is usually finished ina month, or six weeks. I shud be proud of a Line from You; is you please direct for Me Preacher at ye Royal Chapel at Boston in America to be left at ye New England Coffee House near ye Royal Exchange in Cornhill I am Dear Sr, wth ye utmost Deference, & Esteem, yr Honours most obedient, & obliged humble servtt Tho: Harward P.S. I lately recommended a Gentleman to yr prudent Care who has been much disorderd in his Eyes of late, I am affraid there is a Tendency to a Gutta serena. He is a Person of Great Merit, & if a very plentifull estate. He saild for England abt a fortnight ago. P.s. one Thing I had allmost forgott, wch demonstrates ye Amber grease to be ye Excrement of ye whale The spema Ceti whales feed very much of a sort of Fish, wch we call a squid, abt 12, or 16 Inches long, wch a Bill resembling a Hawks, or Parots: And when they take out the Amber grease, they commonly find eithr ye Bone of this Fish, or its Bill, or Both, more or less sticking in ye Amber grease, wch to me is a Proofe of any Contradiction.

Reverend Thomas Harward was a Lecturer at the Royal Chapel in Boston, New England.

Patient Details

-

Patient info

Name: N/A

Gender:

Age: -

Description

-

Diagnosis

-

Treatment

Previous Treatment:

Ongoing Treatment:

Response: -

More information

-

Medical problem reference

![The Hospital of Bethlem [Bedlam] at Moorfields, London: seen from the south, with three people in the foreground. Etching by J. T. Smith after himself, 1814. Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London.](http://sloaneletters.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Bedlam-at-Moorfields-1814-229x300.jpg)

![Statues of "raving" and "melancholy" madness, each reclining on one half of a broken segmental pediment, formerly crowning the gates at Bethlem [Bedlam] Hospital. Engraving by C. Warren, 1808, after C. Cibber, 1680. Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London.](http://sloaneletters.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Figures-in-front-of-Bedlam-300x210.jpg)

![A woman is carrying a tray with a cup of chocolate [or maybe the pleurisy remedy?] and a glass on it. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.](http://sloaneletters.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Cup-of-chocolate-221x300.jpg)