The Story

F. Goya, Three witches or Fates spinning, with bodies of babies tied behind them.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

The tale of Jane Wenham, found guilty of witchcraft in 1712, begins as all early modern witch stories do: with a suspicion.[1] A local farmer, John Chapman had long attributed the strange deaths of local cattle and horses to Wenham’s witchcraft, although he could not prove it. It was not until 1712 that he became sure of her guilt.

On New Year’s Day, Chapman’s servant, Matthew Gilston, was carrying straw outside the barn when Wenham appeared and asked for a pennyworth of straw. Gilston refused and Wenham left, saying “she’d take it”. As Gilston was threshing in the barn on 29 January, “an Old Woman in a Riding-hood or Cloak, he knows not which” asked for a pennyworth of straw. The old woman left muttering at his refusal and Matthew suddenly felt compelled to run to a farm three miles away, where he asked the farmers for some straw. Being refused, “he went farther to some Dung-heaps, and took some Straw from thence”, then took off his shirt and carried the straw home in it.

This was enough evidence for Chapman who “in Heat of Anger call’d [Wenham] a Witch and Bitch”. On 9 February, Wenham went to the local magistrate Sir Henry Chauncy for a warrant for slander, “expecting not only to get something out of [Chapman], but to deter other People from calling her so any more”. Now that the suspicion was in the open, Wenham could try to put the rumours to rest.

Chauncy, however, had “enquired after her Character, and heard a very ill one of her”. He referred the case to the local minister, Rev. Mr. Gardiner on 11 February, who advised them to live peaceably together and ordered Chapman to pay a shilling. Wenham thought this was inadequate; “her Anger was greatly kindled” against the minister and she swore that “if she could not have Justice here, she would have it elsewhere”.

Francis Bragge, another clergyman, stopped by just as Wenham was leaving. Within the hour, the Gardiners’ maidservant Anne Thorn, aged about 17, seemed to become the focus of Wenham’s wrath. The Gardiners and Bragge rushed into the kitchen when they heard a strange noise. There, Thorn was “stript to her Shirt-sleeves, howling, and wringing her Hands in a dismal Manner, and speechless”. She “pointed earnestly to a bundle which lay at her Feet”, which turned out to be oak twigs and leaves wrapped in her gown and apron.

Finally able to speak, Thorn said that “she found a strange Roaming in her Head, (I use her own Expressions,) her Mind run upon Jane Wenham, and she thought she must run some whither; that accordingly she ran up the Close, but look’d back several Times at the House, thinking she should never see it more”. Thorn claimed that she spoke to Wenham, then returned home–all within seven minutes, which meant that she had run over eight miles an hour. This was all the more impressive since she had injured her knee badly the night before. What might have been a wild fancy was verified by two witnesses: John Chapman and Daniel Chapman.

This was only the beginning of Thorn’s torments. The next day, Wenham asked why Thorn lied and warned her: “if you tell any more such Stories of me, it shall be worse for you than it has been yet, and shov’d her with her Hand”. And so she did suffer fron convulsions and pain, compulsions to collect more sticks or to submerge herself in the river, an ability to move quickly despite her injured knee, and a violent desire to draw the witch’s blood.

Wenham claimed that the Devil had come to her in the form of a cat. Here, Beelzebub – portrayed with rabbit ears, a tiger’s face, scaled body, clawed fingers and bird’s legs. (Compendium rarissimum totius Artis Magicae, 1775.) Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Wenham was arrested for witchcraft on 13 February. Four women searched Wenham’s body for witch’s teats or other Devil’s marks, but none were found. A local minister, Mr. Strutt, tried to get her to say the Lord’s Prayer, which she could not do. On 16 February, in the presence of Wenham’s cousin, Strutt and Gardiner took Wenham’s confession. She admitted to bewitching Anne and to entering into a pact with the Devil sixteen years previously, just before her husband’s death.

The trial by jury began on 4 March, presided over by Sir John Powell. Several neighbours gave evidence, blaming the deaths of two bewitched infants and various cattle on her. Some mentioned strange visitations by noisy cats, including one with Wenham’s face. Many described Thorn’s continued convulsions, her pinch marks and bruises from invisible sources, and strange cakes of feathers in Thorn’s pillows. The judge was sceptical throughout. For example, he “wish’d he could see an Enchanted Feather; and seem’d to wonder that none of these strange Cakes were preserv’d”. The jury deliberated for two hours before finding Wenham guilty and sentencing her to death. Justice Powell, however, reversed the death sentence and later obtained a royal pardon for Wenham.

The Pamphlet War

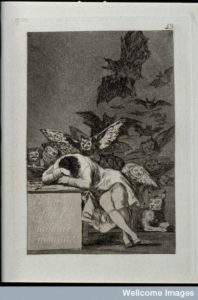

F.Goya, The Sleep of Reason produces monsters.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

In April 1712, Francis Hutchinson wrote to Hans Sloane about the trial, which he had attended. The case was a cause célèbre in England, dividing the educated elite along the lines of rationalism and superstition. On the one side were clergymen such as Bragge, who wrote A full and impartial account of the discovery of sorcery and witchcraft, practis’d by Jane Wenham of Walkerne in Hertfordshire (1712). On the other side were those like Hutchinson, a curate of St. James’s Church in Bury St. Edmunds, who was troubled by the excess of superstition that he had witnessed. Although he shared “some historical Collections and Observations” with Sloane on the subject of witchcraft as early as 1712, it was not until 1718 that Hutchinson published An historical essay concerning witchcraft. Why the delay?

Janet Warner of the Walkern History Society suggests that Hutchinson may have been worried about damaging his own reputation, but I think that the clue is in Hutchinson’s foreword, which he addressed to Sir Peter King, the Lord Chief Justice of Common Pleas, and Sir Thomas Bury, Lord Chief Baron of Exchequer. Hutchinson claimed that he would have continued his historical observations in obscurity “if a new Book [by Richard Boulton], which very likely may do some Mischief, had not lately come forth in Two Volumes, under the pompous Title of A Compleat History of Magick, Sorcery, and Witchcraft, &c.”

Hutchinson feared the public reaction to the book, which promoted the belief in magic and witches. As if people needed more encouragement: Bragge’s Full and impartial account, for example, had gone to four editons within the first month! Such beliefs were dangerous, and not just as a habit of thought, as the events in Walkern had shown. To Hutchinson, the clergymen involved in the Wenham case had behaved irresponsibly, being “as deep in these Notions, even as Hopkins [witchfinder] himself, that hang’d Witches by Dozens”. Instead of preventing superstition from spreading, as Hutchinson intended to do, they had taken a leading role in encouraging it.

Afterword

It was obvious that Wenham could no longer remain in Walkern, given the town’s insistence that she was guilty. Captain John Plummer was described by Hutchinson as a “sensible man” for taking Wenham under his protection—“that she might not afterward be torn to peeces”. Wenham lived there “soberly and inoffensively” until 1720 when Plummer died. She lived another ten years under the care of William Cowper, the 1st Earl of Cowper, dying at the age of 90.[2]

[1] This account is taken from Francis Bragge, A full and impartial account of the discovery of sorcery and witchcraft, practis’d by Jane Wenham of Walkerne in Hertfordshire, upon the Bodies of Anne Thorn, Anne Street, &c. (1712). (Yes, this is the same Francis Bragge who gave testimony in the case!)

[2] Both men were also correspondents of Hans Sloane’s.