This past week has been an exciting time for portents! What with a meteor blasting into Russia, an asteriod passing close to earth, St. Peter’s Basilica being struck by lightning, and the Pope resigning, early modern people would have been getting a bit nervous…[1] As it is, some people believe that the lightning strike was a sign that God approves the Pope’s decision. Perhaps we live in a more optimistic era.

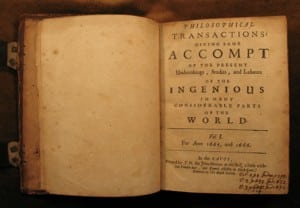

There are several letters in the Sloane Correspondence database about early modern astronomy, although only two that mention comets.[2] By the eighteenth century, there was a growing shift away from seeing dramatic astronomical events as portents. Clergyman William Derham (1657-1735), for example, wrote to Sloane regularly about natural philosophy and his letters (dated 28 March 1706) reveal a careful attention to matters of fact rather than a concern with religious signs.[3]

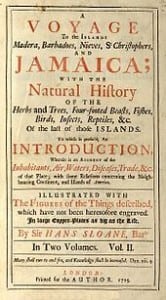

“Part of a Letter from the Reverend Mr W Derham, F.R.S. Concerning a Glade of Light Observed in the Heavens”. Philosophical Transactions, vol. 25, no. 305 (1706), p. 2221.

In one of Derham’s letters, which also appeared in the Philosophical Transactions (vol. 25, 1706), he described his star-gazing just before Easter. While observing the satellites of Saturn, he spotted a “glade of light” in the constellation of Taurus. The light had a tail like a comet, but a pointy upper end instead of a rounded one. This, Derham was certain, was similar to what Joshua Childrey and Giovanni Domenico Cassini had observed. When the following nights were cloudy, Derham was unable to spot the glade again–and, although Easter Day was fair, he “forgot it unluckily then”. By the time he was next able to look at the skies, the glade of light was gone.

This was the only bit of Derham’s rather long letter that was published in the Phil. Trans. this time. In the letter, Derham also dicussed sunspots and requested advice about his wife’s eye problems. This was typical of many of Sloane’s correspondents, whose letters blurred the boundaries between scholarly, social and medical matters.

Anna Derham, aged about 31, was suffering from eye problems. Sloane had recommended that she take a variety of medicines, including a purge (and rather revoltingly, woodlice), in addition to eye drops. The eye drops, Derham reported, did not agree with his wife and had caused an inflammation. The purge, moreover, had left Mrs. Derham with violent pains spreading from above her eye to throughout her head and face. Derham believed that the eye medicine had resulted in his wife’s cornea wasting away. The outcome of the eye problem was not noted, but a letter from later that year (30 August 1706) mentioned Mrs. Derham’s increasingly severe headaches, which worried both her and her husband. Whether her health improved (or Derham simply distrusted Sloane’s advice in this case) is unclear, but Derham did not mention his wife’s health again until November 1710 when he feared that she might die from peripneumonia. (Mrs. Derham didn’t, managing to outlive her husband.)

What strikes me as particularly interesting in Derham’s account is the small detail that he forgot to look at the skies on Easter Sunday. As a clergyman, he was no doubt very busy in the week leading up to and including Easter. It would be entirely understandable that he might forget… but he did manage to look out his telescope in the nights prior to Easter.

The rather pressing matter of his wife’s health, on the other hand, is the most likely reason. It’s clear that her symptoms were alarming and disabling (as would have been the treatments, as purges kept one very close to the chamberpot). To compound the domestic disruption, the couple had four children between the ages of two and six in 1706. At the very least, Derham was monitoring his wife’s health and overseeing her medical care.[4] Even with domestic help, Mrs. Derham’s poor health would have posed a challenge for the household at the best of times, but even more so at the busiest time of year for a clergyman’s family.

Early modern scientific endeavours often took place within the early modern household, meaning that these activities were inevitably subject to the rhythms and disruptions of daily life. With his ill wife, several young children, and Easter duties, Derham simply did not have time to remember.

[1] For other recent blogging on historical comets, see Darin Hayton on “Meteorites and Comets in Pre-Modern Europe” and Rupert Baker on the comets in the Philosophical Transactions (“Watch the Skies“).

[2] The other letter was from Leibniz (5 May 1702), which was an account in Latin of a newly discovered comet.

[3] On Derham and his family, see Marja Smolenaars, “Derham, William (1657-1735)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7528, accessed 7 June 2011.]

[4] For more on men’s medical caregiving roles within the family, see my article “The Relative Duties of a Man: Domestic Medicine in England and France, ca. 1685-1740”, Journal of Family History 31, 3 (2006): 237-256.