Michael Maittaire to Hans Sloane – July 25, 1731

Item info

Date: July 25, 1731 Author: Michael Maittaire Recipient: Hans SloaneLibrary: British Library, London Manuscript: Sloane MS 4051 Folio: ff. 282-283

-

Language

English

-

Library

British Library, London

-

Categories

Library, Patronage, Scholarship, Trade or Commodities, Travel

-

Subjects

Books, Manuscripts, Publishing, Subscriptions

-

Date (as written)

July 25, 1731

-

Standardised date

-

Origin (as written)

-

Others mentioned

Edmond Halley

-

Patients mentioned

Original Page

Transcription

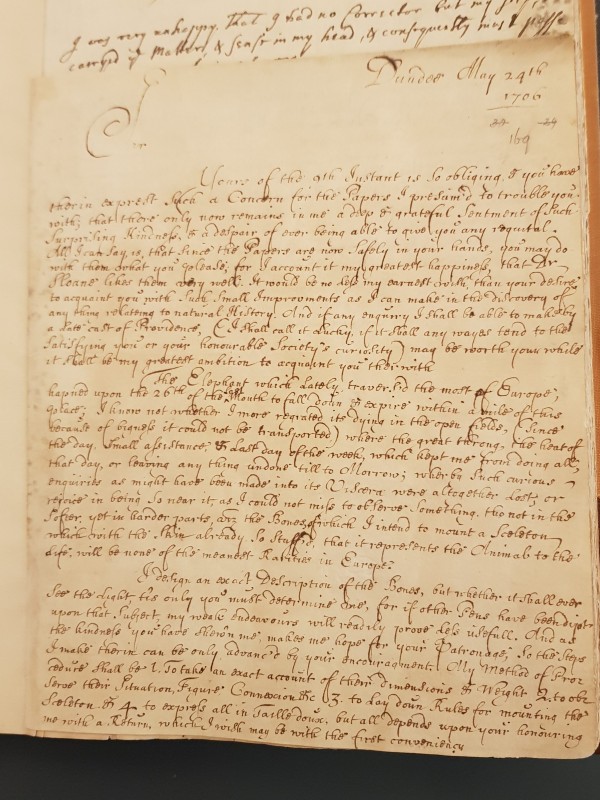

[fol. 282] 1731. July ye 25 Hond Sir, I am very much obliged to you for your accustomed communicative temper; which I wish all learned men were endow’d with. I don’t doubt but you’l secure the valuable MS. you mention for your Library, which ough to want nothing that is good and rare. The next opportunity I have of coming to town, I’l take the liberty of waiting on you, and viewing it. The printed books of the Oxford Marbles have indeed many faults, which could not escape the eyes of so sagacious a man as Dr Halley. I receiv’d by this Post a Proof of my edition of the Marbles, wch I am now sending back corrected. The numbers of the pages of that sheet are 637, 638, 639, 640. By which you may perceive, how many sheets we have finished. Our family here is in very much hurry. The Dutchess was yesterday morning taken ill of a sudden. Give me leave to subscribe myself, Worthy Sir, with much gratitude and respect, Your most obedient and most humble servt MMaittaire I must also acquaint you, that I am hard at work upon a tedious and long Index to my Annales Typographici. ‘Tis written fair as farr as the Letter G.

Michael Maittaire was a classical scholar, typographer, and schoolmaster. He was educated at Westminster School and and Christ Church, Oxford. Mattaire was under-master at Westminster School from 1695 to 1699 before founding his own private school at Mile End. He published editions of Latin and Greek classics throughout his scholarly career and had an extensive library (Margaret Clunies Ross, Amanda J. Collins, Maittaire, Michael (16681747), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/17841, accessed 16 Aug 2013]).

Patient Details

-

Patient info

Name: N/A

Gender:

Age: -

Description

-

Diagnosis

-

Treatment

Previous Treatment:

Ongoing Treatment:

Response: -

More information

-

Medical problem reference